Tags

Campbell River, Cowichan Lake, Denman Island, Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson, Duncan, fishing tackle, Henry Layard, salmon trolling, tyee fishing, Victoria

Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson, veteran of the Bengal Army, retired to Vancouver Island and California where he pursued his passion for big-game fishing, setting two salmon-angling world records at Campbell River in 1903.

In the late 1880s, Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson, a retired English army surgeon and veteran of the Bengal Army, joined an established community of soldiers’ families who had come from India to settle on Vancouver Island. They were attracted in part by the excellent trout and salmon fishing on the Cowichan River and at Cowichan Lake. After more than a decade in the Cowichan Valley, Dr. Dickson purchased a property on Denman Island and a house in Victoria, wintering in California where he was exposed to the new pastime of big-game fishing that was sweeping the sporting world. He then embraced and helped to publicize the recently launched tyee (Chinook salmon) sport fishery at Campbell River in the first years of the 20th century. Bringing his knowledge of angling for large salmon from Monterey Bay to Campbell River, he was considered an authority on tackle and patented a reel of his own design. He established two salmon-angling world records at Campbell River in 1903, and wrote about his experiences of tyee fishing in the British sporting magazine, The Field: The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper.

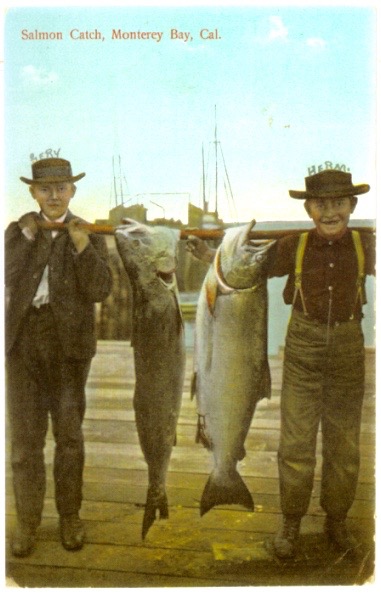

Early-20th-century postcard promoting angling for King (Chinook) salmon at Monterey Bay, California.

Frederick Lindsay Dickson was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1834, to Scottish parents. His father, Dr. Samuel Dickson, was a prominent London surgeon who helped to revolutionize the practice of medicine by waging a long and unpopular campaign against bloodletting—standard medical practice for most ailments in the 1830s. Drawing on observations based on his five years’ service as a young Army surgeon in India, Dr. Samuel Dickson came to believe that bloodletting weakened patients; he advocated instead the use of stimulants such as quinine and alcohol. Lindsay Dickson followed in his father’s footsteps, taking medical training at the University of Aberdeen. According to his obituary in the British Medical Journal (August 20, 1908), “he joined the Bengal Medical Department as Assistant Surgeon, August 4th, 1857; was made Brigade-Surgeon, November 27th, 1882; and retired from the service in the following year.” In 1869, Dr. Dickson married Charlotte Kirkpatrick in Edinburgh; she was the daughter of John Kirkpatrick, a prominent Edinburgh advocate and former Chief Justice of the United States of the Ionian Islands. The Dicksons settled in India; three of their six children born over the next decade died at a very young age. The misery of the heat and the threat to the survival of their children finally drove them to leave India.

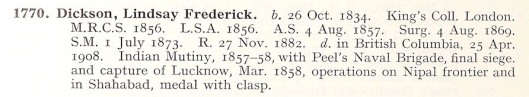

Service record of Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson. Source: Lieut.-Colonel D.G. Crawford, comp. Roll of the Indian Medical Service, 1615-1930. London: W. Thacker, 1930. Accessed using Ancestry.com.

Although Dr. Dickson’s military records indicate that he retired from the Indian Medical Service in 1882, by that time the family had already relocated to Australia. The Register of Medical Practitioners for 1885 in the Victoria Police Gazette (February 4, 1885) indicates that Dr. Dickson first registered as a medical practitioner in Melbourne on May 7, 1880. The two youngest surviving Dickson children were born in Australia in 1881.

After at least five years in Australia, Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson and his family came to settle on Vancouver Island. By this time, the Island was already becoming known as a destination attractive to veterans of the Imperial Army, especially those who had served in India and wished to retire to a more healthful climate. With cheap farmland, abundant fish and game, a temperate climate, and scenery to rival anything in Great Britain, Vancouver Island offered the prospect of a comfortable and congenial existence to former soldiers and their families who faced retirement on meagre pensions. Many veterans like Dr. Dickson had developed a taste for field sports during their years of foreign travel and military service, and Vancouver Island promised unparalleled opportunities for hunting, shooting, and fishing.

The arrival of the Dickson family on Vancouver Island coincided with the opening up of the Cowichan Valley for farming and logging. The small community of Duncan, on Cowichan Bay at the mouth of the river, had been connected to Victoria by the completion of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway line in 1886. Soon after, the first wagon road to the lake was constructed, beginning at the Quamichan Hotel at Duncan’s Station. Among the first settlers on the lake were the brothers Charles and Alfred Green, who opened the Cowichan Lake Hotel in 1887—a log structure for the accommodation of sportsmen. Advertisements for the hotel first appeared in the Victoria Daily Colonist in June 1887; on August 26, the paper’s “Cowichan Lake Notes” recorded that “Dr. Dickson is having a good time with the salmon this week. He has landed several very fine specimens, the largest being twenty pounds.” This is the earliest reference to F. Lindsay Dickson in the Colonist. The family may have settled in Victoria initially, with Dr. Dickson being among the city’s anglers who regularly took the train to the Cowichan. Henderson’s BC Gazetteer and Directory for 1889 lists the Victoria residence of Lindsay Dickson, M.D., as 1 Richardson Street at the corner of Vancouver Street.

Victoria Colonist, June 5, 1887

Proprietors Charles and Alfred Green at the Cowichan Lake Hotel, ca. 1887, probably with their siblings Frank and Annie. Image E-02541 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

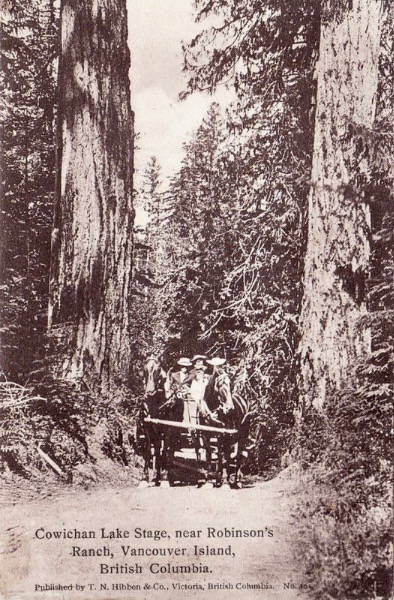

Lindsay Dickson may have arrived on Vancouver Island with a dream of running a hotel catering to sportsmen or he may simply have seen an opportunity when the Green brothers decided to put their hotel up for sale. In 1889, Dr. Dickson purchased the Cowichan Lake Hotel, apparently with the goal of expanding and upgrading the accommodations to suit families as well as sportsmen. On September 22, 1889, the Colonist included in its Sunday Supplement a lengthy description of the tourist delights awaiting the Victoria visitor at “Great Cowitchan Lake.” Earlier that summer, the author, “G.G.,” had paid a visit to the lake and to “Doctor Dickson’s new hotel, situated at the entrance to the lake, or rather, on the left bank of the river, a quarter of a mile from where it leaves the lake.” After a charming two-hour train ride to Duncan’s, the visitor could continue by wagon over 21 miles of “good forest road” to the lake, or the strong and active lover of nature could walk; “Dr. Dickson’s conveyance receives passengers as well as freight every second day.” The walk left G.G. seemingly overwhelmed by the sylvan splendour and cathedral-like silence of the primeval forest, and he advised the prospective visitor to experience this salubrious wonder before its imminent transformation into cornfields and orchards.

On reaching Dr. Dickson’s place, the tourist sees the river just preparing for its journey to the ocean, and he will certainly not fail to linger there to bid it farewell before proceeding on his excursion round the lake. There will be accommodation for any number of tourists, in the future, at the ‘Cowitchan Lake Hotel,’ for a new building has been erected by the side of the hunting lodge which formerly offered but limited space to travellers, and the present proprietor intends stocking his house with only first class articles so that the tourist will miss none of the town comforts, when the hotel is completely finished.

The remainder of G.G.’s account describes an excursion around the lake, taking five or six days in a rowboat hired at the hotel and camping at recommended sites with splendid views and opportunities for sport along the way.

Victoria Colonist, August 15, 1889

Postcard view of the lake road and stage connection from the Quamichan Hotel at Duncan’s Station to the Cowichan Lake Hotel (later the Riverside Hotel). Simon Fraser University Library, BC Postcard Collection, MSC130-13490.

Dr. Dickson must have sold the house in Victoria and moved the family to Duncan in 1889. According to the above advertisement in the Colonist, he arranged that the well-known Victoria gunsmith and dealer in sporting goods, Henry Short, would inform visitors to his store at 32 Fort Street about the hotel accommodation and transportation to Cowichan Lake. Despite the ambitious plans described in G.G.’s account, within a year Dr. Dickson had leased or sold the hotel to Angus Fraser. Whether the entire Dickson family had moved to the hotel or remained in Duncan is unclear, but they would have led an isolated existence at Cowichan Lake. Possibly the doctor’s wife and three growing daughters preferred the social and cultural opportunities offered by life in the thriving community of Duncan at the other end of the river. After the move from Victoria, a residence in Duncan may have been a compromise that suited everyone.

Dr. Dickson purchased a property on Quamichan Lake, just outside Duncan, at the beginning of what local historian Tom Henry has described as Duncan’s “era of the Longstockings.” Quamichan, with its concentrated population of retired British army officers, was one of several British enclaves. Beginning in 1890, snippets of news from the Daily Colonist suggest that Dr. Dickson was quickly integrated into Duncan society. As a retired Brigade Surgeon and Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (England), he was respected as a medical authority and his expertise was sought by provincial legal and public health officials. At the time of a local smallpox outbreak in 1892, Dr. Dickson, who undoubtedly had experience with vaccination in India, was appointed Municipal Health Officer and Public Vaccinator for the Cowichan District. He held public vaccination days and arranged to meet passengers arriving on the incoming train at the Quamichan Hotel every morning in July. Between 1890 and 1893, he served as medical examiner and testified at inquests in several cases of accidental or unexplained death. In October 1891, for example, he canoed forty miles to Saturna Island to conduct a postmortem examination of an unfortunate man who had removed himself from Victoria “for the purpose of getting off a drunk” and then died from a fall during an attack of delerium tremens.

Early-20th-century postcard view of Quamichan Lake. Simon Fraser University Library, BC Postcard Collection MSC 130-11554.

At the Cowichan and Salt Spring Island Agricultural Show in September 1895, Dr. Dickson competed successfully in the categories of Horses (special prize for single turnout) and Fruits (second prize for winter pears). In April 1896, he accompanied one of his daughters, a “Scotch girl,” to the Cowichan Football Club’s fancy dress ball at the Agricultural Hall; Dr. Dickson was imaginatively costumed as an “army surgeon.” He also found many opportunities to indulge in fly fishing for trout right on his doorstep at Quamichan Lake.

The Rod. The Premium Trout. Duncan, May 7. –(Special)—Hon. F.G. Vernon, A.W. Vowell, A.W. Jones, W.F. Burton, N.P. Snowden, Sir R. Musgrave, and Lindley Crease, arrived from Victoria on Saturday with their fishing tackle. Trout appear to be taking more cleverly in the rivers and lakes. Dr. L.F. Dickson procured the largest trout of the year so far, almost a week ago, in Quamichan Lake, weight—4 lbs. 2 oz. (Victoria Colonist, May 8, 1894)

Dr. Dickson reports having secured several excellent trout of three pounds each and over, in Quamichan Lake. (Victoria Colonist, May 21, 1895)

Trout are now in good season at Cowichan lake and plentiful, and steelheads, silver salmon and trout are being taken daily in the Cowichan river. Mr. Leather recently made the fly-fishers’ record in Quamichan lake with ten trout weighing over twenty pounds. Dr. Dickson, during the same week, caught several good fish, the heaviest scaling about three and a quarter pounds. (Victoria Colonist, May 2, 1896)

Dr. and Mrs. Dickson clearly had a penchant for travel (an inclination that may have proven incompatible with hotel ownership). They left the Cowichan for a three-month visit to England and Auld Reekie (Edinburgh) at the end of 1892; their son, Frank, had just begun his studies at the University of Glasgow. On May 2, 1894, the Colonist reported that they had just returned from Japan on the CPR liner Empress of China.

Victoria Colonist, May 11, 1898

On March 13, 1898, the Colonist reported, “Dr. F.L. Dickson, who returned to Duncan from Los Gatos, California, on Thursday last, left again on this morning’s train for Victoria en route by the C.P.R. for England.” In 1897 Dr. and Mrs. Dickson had uprooted themselves yet again, this time moving to Santa Cruz, California, where they were living at the time of the US Federal Census in 1900 with their youngest children, Gerald and Amy. For the next few years Dr. and Mrs. Dickson spent their winters in California and their summers on Vancouver Island. By this time, their children were fully grown and Dr. Dickson was free to devote himself to angling—the dominating passion of his final years.

Around 1900, the Dicksons purchased a large farm and wooded property on Denman Island, one of the Northern Gulf Islands and today part of the Comox Valley Regional District. In 1878, this property had been taken up by the family of John Graham from New Brunswick; the Grahams ran a small dairy farm, hand logged part of the property, and planted a small orchard. A major attraction for Dr. Dickson was Graham Lake, bordering on the property and offering excellent trout fishing. Within a few years, the Dicksons had turned the farm over to their son Gerald, who married a local girl and raised a family on Denman Island, living in the old Graham farmhouse. In 1923, a beautiful Arts and Crafts house that still stands on East Road was built for the family of Gerald Lindsay Dickson. By 1905, Dr. and Mrs. Dickson had purchased a house in Victoria at 8 Pemberton Road near Craigdarroch Castle.

In 1923, this Arts and Crafts house on East Road, Denman Island, was built for Dr. Dickson’s son, Gerald Lindsay Dickson. Photo by John Millen.

Graham Lake, Denman Island–a favorite fishing spot of Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson–from the southwest corner of the Lindsay Dickson Nature Reserve. Today the lake supplies water to 70 households and still contains cutthroat trout. Photo by John Millen.

The Dicksons’ decision to establish a winter residence in Santa Cruz, at the northern end of Monterey Bay, must have been another happy compromise that would have satisfied all members of the family. By 1897, Santa Cruz was a thriving and fashionable year-round resort whose attractions included mountain scenery and ancient redwood forests, hotels and sandy beaches, Italianate-style architecture, a boardwalk, and the largest swimming baths west of the Mississippi; the highlight of the season was the annual Venetian Water Carnival that was launched in 1895. Best of all for Dr. Dickson was Santa Cruz’s standing as one of the pre-eminent fishing resorts on the Pacific Coast. Close to many mountain streams, the city was located at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River, then considered the best angling river in Central California, especially popular for its steelhead trout and large coho salmon.

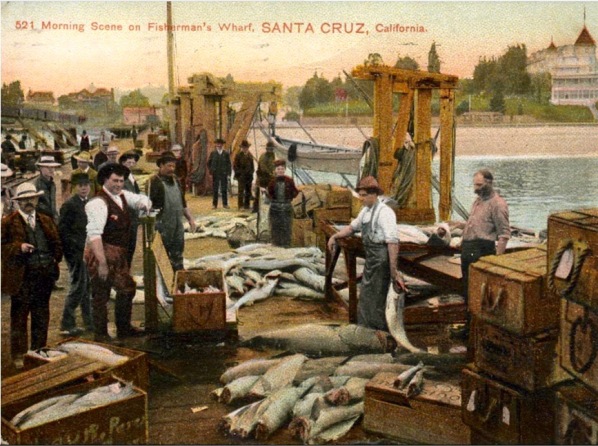

Monterey Bay was the centre of California’s fishing industry and there were plenty of sea-fishing opportunities for the sportsman who could hire a visitor’s chair on a fishing boat and accompany the fleet. And California, along with Florida, was home to the new international sport of big-game fishing, which included trolling with a rod and line for the large King (Chinook) salmon that congregated in Monterey Bay to feed on anchovies before migrating upriver. Possibly Dr. Dickson was able to visit the island of Santa Catalina, the base of the prestigious Tuna Club of Avalon founded in 1898. He would certainly have been aware of the philosophy of the Tuna Club and its challenge to wealthy sportsmen to take large and powerful fish around the globe by “sporting” means—with a rod and line, rather than with handlines, nets, spears, guns, and other methods that, in the hands of “so-called sportsmen,” often led to the indiscriminate and wasteful slaughter of fish.

Postcard view of Fishermen’s Wharf, Santa Cruz, ca 1909. Source: Julia Gaudinski, “The Santa Cruz Wharf: A Hundred Years of History,” Mobile Ranger: Connecting People to Places (blog), July 27, 2014, http://www.mobileranger.com/santacruz/the-santa-cruz-wharf-a-hundred-years-of-history/

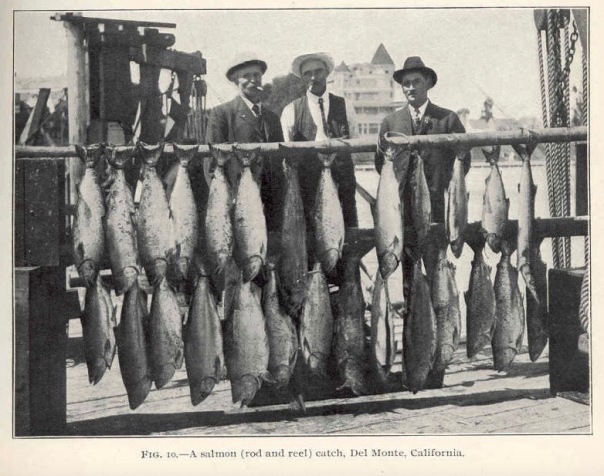

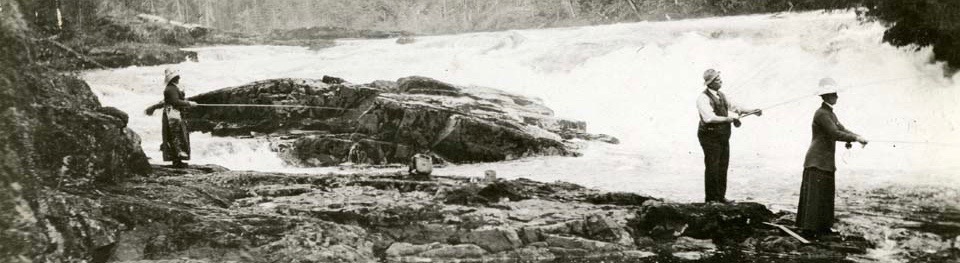

Wealthy anglers pose with salmon taken with a rod and line, Del Monte (now part of the City of Monterey), Monterey Bay, 1908. Charles F. Holder, Sportfishing in California and Florida. Washington, DC : Government Printing Office, 1910. University of Washington Libraries, Freshwater and Marine Image Bank.

In the midst of the global excitement over big-game fishing among members of the international angling fraternity, Vancouver Island’s Campbell River had been catapulted to fame by Sir Richard Musgrave’s capture of a 70-pound Chinook salmon in 1896—a world record with a rod and line. After five years of angling experience at Monterey Bay, Dr. Dickson made two trips to Campbell River, in the summers of 1902 and 1903, that he described in “Salmon Fishing on a Large Scale”—an article published in the British sporting magazine, The Field: The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper, on February 11, 1905.* This is a significant account of the early days of the sport fishery at Campbell River, before the construction of the Willows Hotel and the cannery at Quathiaski Cove in 1904 and the new wharf in 1907 that turned Campbell River into a regular stop for coastal steamships.

Dr. Dickson was anxious to assure the Field’s readers, including dubious British anglers who were not attracted by salmon trolling, that they would find Vancouver Island’s “monsters” to be worthy foes. At Campbell River he had observed that “even the best and most experienced of fishers, with the strongest of tackle, are constantly coming to grief,” and he was keen to share what he had learned elsewhere about innovations in tackle for this challenging new game fish. He took with him “three dozen spoons and spinners of various sorts, being most successful, as it happened, with some of my own making, among which were several made of the California ‘abilone’ shell.” Although most anglers he encountered were using a 10-foot to 12-foot rod, Dr. Dickson preferred a 16-foot greenheart rod with two feet removed from its tip. He recommended bringing a spare middle joint, as his had broken from the strain after taking 80 of the “big fellows.”

The Campbell salmon are, I fancy, the largest in the world. There are several of the rivers farther north which hold salmon, but, strangely enough there they will scarcely ever take a spoon as they do in the Campbell. They are the kind called by the Indians ‘tyhee,’ or ‘chief’ and are very much like the salmon of Britain. It is only during the last five or six years that anyone has taken to fishing for them with a rod, but now that they have done so there are more and more people going up there every season, including parties from the British warships, particularly the torpedo boats, steam launches from Victoria, yachts from the States, and globe trotters from everywhere.

Dr. Dickson’s first trip to Campbell River in August 1902, travelling from Victoria on the steamer Boscowitz, was an inauspicious introduction to tyee fishing. His party arrived too late in the season and wasted a week camping some distance up the river where they could not get in or out except at high tide because of dangerous rocks. No sooner did they leave this location than “a school of whales came into the sound, about ten or twelve in number, and drove the salmon completely out of it.” The “mischievous” whales (orcas) spent four or five days rushing up and down the sound (Discovery Passage), roaring through their blowholes, and flinging themselves into the air with thunderous splashes. The salmon, concluded Dr. Dickson, “retreated up the river and stayed there until the whales departed … [I]t was no use to go fishing.” He withdrew across the sound to the settlement at Quathiaski Cove where he had to wait five days for the return of the steamer and console himself with fishing for coho.

Having been “sufficiently convinced that good sport was to be got here,” Dr. Dickson returned to Campbell River, again on the Bowcowitz, at the end of July 1903. According to his account, he tried to engage two Japanese fishermen to take turns to cook and row for him, but “they were all engaged to row for the different canneries. I had, therefore, to put up with two Chinese, who said that they could row.” His Chinese helpers turned out to be unable to handle a boat and they quit in frustration after five or six days. Dr. Dickson persuaded one of them to stay on as cook and “managed to get a brother of the storekeeper to row for me, after which I changed my position from where I was, about a mile and a half from the river’s mouth, to a little logger’s shanty close to it, and from that time on got far better sport.” Small wonder that Dr. Dickson’s luck changed at this point! His boatman was one of the Pidcock boys from Quathiaski Cove, the sons of Indian Agent Reginald Pidcock, who knew the local waters, had handled boats from an early age, and were skilled in the traditional technique of taking tyee salmon with handlines and spoons as practised by the local Lekwiltok people. Dr. Dickson must have been camped on Discovery Passage at the site of the soon-to-be-built Willows Hotel and moved, no doubt on the advice of his boatman, to the waters off the Spit at the mouth of the river, today known as the Tyee Pool.

The author on the Spit at the mouth of the Campbell River, adjacent to the Tyee Pool, with the famous fishing resort, Painter’s Lodge, in the distance, October 2009.

The remainder of Dr. Dickson’s article in the Field consists of extracts from his fishing diary for August 2 to August 27, 1903, when he fished every morning and evening except Sundays and several days of stormy weather. He provides the number of fish caught each day and the weight of each fish, sometimes also mentioning fish that he lost. During this trip, Dr. Dickson established two salmon-angling world records, later confirmed by the Field. The first was for the greatest weight of salmon caught in one day with a rod—12 tyee salmon weighing a total of 458 pounds. The second was for the greatest weight of salmon caught with a rod in 16 days of fishing—92 tyee salmon weighing 3,665 pounds with approximately 100 smaller salmon that were mostly thrown back in the water, for a total weight of more than two tons.

Dr. Dickson was disappointed that he was not able to break the record for largest fish set by Sir Richard Musgrave but he did catch one “splendid fellow” who would have weighed over 60 pounds if he had not been left in the blazing sun for several hours before being weighed; one of the anglers had taken the steelyard and left it in his tent. “I left him on view (together with the steelyard) in a little house on the point, where most of the fishers were encamped, and where many of us left our take to compare with that of the others, and afterwards gave them away to the Indians.” The anglers offered their surplus catch, to be dried for winter food supplies, in exchange for the privilege of camping on the spit at the mouth of the river, which was then part of Campbell River Indian Reserve No. 1.

Dr. Dickson was not optimistic about the future of the fishery at Campbell River, “as a cannery is said to be going up, and in that case the seine nets will ruin the rod fishing in a very short time.” Still, he concluded his account in the Field with his recommendations for tackle.

Up to this time [August 8, 1903] I had been fishing with what I had bought in California as ‘tarpon’ line. I found it, however, the veriest rubbish, and it broke up in the most exasperating manner. I had to buy some coarser line from the little store at Quathiaski, and afterwards lost fewer fish, though these big fellows are ‘death’ on tackle, and spoons, &c., were quite at a premium amongst my brother anglers …. For the benefit of anyone who thinks of making this trip I would say: Bring a 5 in. reel (or two), with at least 180 yards of strong line—200 yards is preferable if your reel will hold it, as you have to fish very deep, and with quite 50 yards out behind the boat, and as close as you can to the bottom, where the big fish usually lie; at least half a dozen boat-shaped leads of 8 oz. and 10 oz., traces of the strongest, and a good supply of long-shaped spoons from 3½ in. to 4½ in. long and from 1½ in. to 1¾ in. wide. You require also a special gaff, fully twice the size of what is usual and of twice the thickness.

This beautiful brass salmon lure, measuring 3 5/8″/93 mm, once belonged to Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson. Courtesy of Gary Luney.

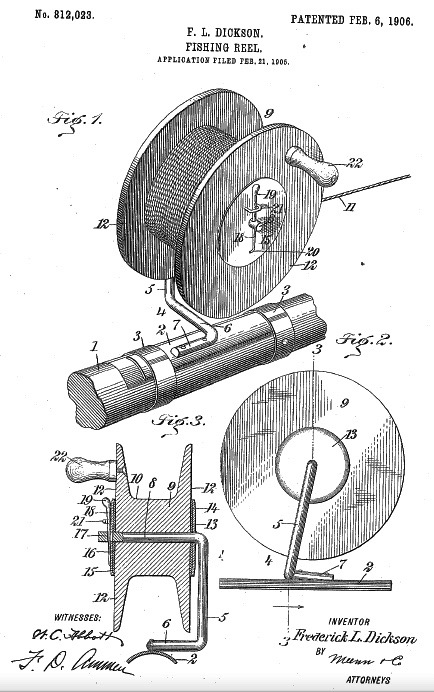

On August 12, 1905, the Victoria Colonist reported that Dr. Dickson was back at Campbell River, engaged in a well-publicized competition with another experienced British angler, Henry Layard. Both had spent the previous three summers fishing at Campbell River. Their objective was to establish world records for the largest bags of coho (Layard) and tyee (Dickson) taken with a rod and line in a two-week period; unfortunately the results were not published in the Colonist. By this time, the paper noted, “Dr. Dixon[sic] has given so much attention to tyhee fishing that he has been able to invent a reel and put it on the market, that is perhaps the only safe reel to use in playing this heavy weight marine fighter. It is worked by washers and a peg tapering to a point, and the peg gets a tremendous purchase in paying out the line, so that it can be made to run fast or slow at the slightest pressure.” In February 1905, Dr. Dickson applied for a patent on his “new and Improved Fishing-Reel” of the type “used by anglers for ‘playing’ a fish after it has been struck.” The object of his invention was “to produce a reel of simple construction which is provided with means for controlling at any instant the tension of the line in unwinding.”

F. Lindsay Dickson was granted a patent for a fishing reel of his own design in February 1906. Source: http://www.google.com/patents/US812023

Lindsay Dickson also indulged his passion for fly fishing while at Campbell River. He was well known for tying his own flies, and at least one of his creations remained popular after his death. On August 4, 1912, a Victoria Colonist editorial recommending a trip through the relatively unknown country between Nanaimo and Campbell River, reported the use of Dr. Dixon[sic], Old Ginger, Governor, and Zulu by trout anglers on the Campbell River.

After 1905, Lindsay Dickson maintained his house in Victoria but travelled extensively, visiting his children and their families. In 1907, his youngest child, Gerald Lindsay Dickson, who had attended an English public school and McGill University, married Laura Keenan, from a Denman Island family, and settled on the Lindsay Dickson property. In Glasgow, Gerald’s older brother, Dr. Frank Lindsay Dickson, had married Margaret Telfer Kirk Houston in 1898, and then settled on the Isle of Wight in England. Madeline, the firstborn, had married an English actor, Hugh George Oughterson, in 1899 and was living in London. In February 1905, Lindsay Dickson applied to patent his fishing reel in El Paso, Texas, where his daughter Amy was about to marry another British Columbian, mining engineer Robert Musgrave. His remaining daughter Charlotte had married Reginald Hooper in 1897, settling first in Santa Cruz and then in Ventura, California.

Back in Victoria, on February 1, 1907, the Colonist published the list of distinguished invitees to a grand ball hosted at Government House by His Honour the Lieutenant Governor James Dunsmuir and Mrs. Dunsmuir the previous evening. Among the 300 couples named were “Brigade Surgeon Lieut.-Col. F. Lindsay Dickson and Mrs. L. Dickson.” Whether the Dicksons actually attended the ball is unclear because Charlotte Dickson, who had diabetes, had been in failing health for some time. Several days after the ball, she died at St. Joseph’s Hospital at the age of 64. She was buried in Victoria at Ross Bay Cemetery (B 74/75 W 38).

Dickson monument, Ross Bay Cemetery, Victoria. Photo by author.

A little over a year after Charlotte’s death, Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson, a confirmed pipe smoker, died on Denman Island at the age of 74 from cancer of the larynx. Like Charlotte, he had a well-attended funeral in Victoria at Christ Church Cathedral and he was buried with her in the family plot at Ross Bay Cemetery. By that time, however, he had embarked on a second marriage with Derbyshire-born Elizabeth “Essie” Beardsley, a 43-year-old hospital-trained nurse. Essie had been hired by the Dicksons to care for Charlotte as her health deteriorated and had probably been living with the family for some time. Her previous residence was Brighton, Hove, England, where she had two sisters, one of whom was also a nurse. Dr. Dickson’s second marriage was registered in October 1907 in Leicestershire, England; it may have taken place at the home of his younger sister, Madeline Bennie.

Whether this last-minute second marriage generated tensions within the Dickson family is unknown, but the doctor and his new wife seem to have spent their time together visiting his children and their families. Since the doctor was ill with cancer, he may have needed care himself so that he could continue to travel. Returning from England in October 1907, Lindsay and Elizabeth Dickson passed through Quebec City on their way to British Columbia. They then travelled to Sonora, Mexico, for an extended visit with Amy and Robert Musgrave, the latter being employed at the El Tigre mine. They may have visited the Hoopers in California en route. On March 18, 1908, the Dicksons re-entered the United States at Douglas, Arizona, stating their destination as Denman’s Island, British Columbia. On April 25, 1908, Dr. Dickson died at the family property on Denman Island during a visit with Gerald and Laura Dickson. His body was returned to Victoria by boat for the funeral on May 4.

According to the US Federal Census of 1910, the widowed Elizabeth Dickson was living with the family of her stepdaughter, Amy Musgrave, in Santa Cruz; her place in the family was identified as “mother.” On September 12, 1911, likely still living with the Musgraves, Elizabeth Lindsay Dickson died from septicemia cholecystitis in Mexico City, where she was cremated. During her illness, she received financial assistance from members of the Musgrave and Hooper families; probate was handled by John Musgrave of Victoria.

At the time of his death in 1908, Dr. F. Lindsay Dickson owned property in several locations including Victoria, New Westminster, the Cowichan District, and Denman Island. With the exception of the holdings on Denman Island, the property was sold, with the proceeds going to his various heirs, including his second wife; he provided generously for his grandchildren. Gerald Lindsay Dickson received two pieces of land and some livestock, valued at $4,100. This Denman Island property passed to Gerald’s son Clive and was enjoyed as a family summer retreat by several generations of the descendants of Lindsay and Charlotte Dickson until it was sold in 1993. By that time, because most of the property had never been logged, it had been targeted for possible protection by the Denman Conservancy Association, formed in 1991 (http://www.denman-conservancy.org).

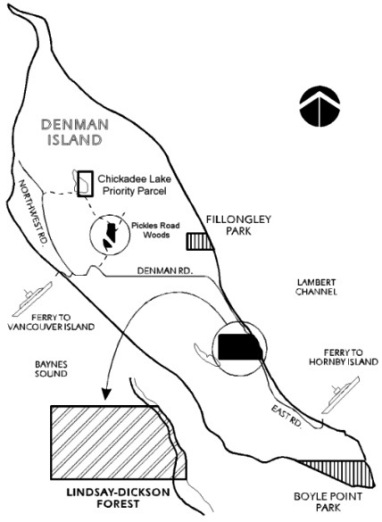

After a 10-year campaign by the Denman Conservancy Association, 134 acres of forested land and foreshore, part of the original Lindsay Dickson estate, was purchased by the Province of British Columbia in 2001 and transferred to the Islands Trust fund. It is now managed by the Denman Conservancy Association and is known as the Lindsay Dickson Nature Reserve (http://www.denman-conservancy.org/our-work/lands/lindsay-dickson-n-r/).

Denman Island, showing location of Lindsay-Dickson Forest adjacent to Graham Lake, with permission of the Denman Conservancy Association.

Lindsay-Dickson Nature Reserve, Denman Island. Photo by Andrew Fyson, with permission of the Denman Conservancy Association.

Lindsay-Dickson Nature Reserve, Denman Island. Photo by Peter Karsten, with permission of the Denman Conservancy Association.

*Lindsay Dickson, Brigade Surgeon. “Salmon Fishing on a Large Scale.” The Field: The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper No. 2720 (February 11, 1905). Photocopy and typed transcript, Sportfishing file, Museum at Campbell River Archives.

Thanks to Nancy Hughes and Chandar Sundaram for helpful responses to queries, and to angler Jim Askey for pointers on the subject of tackle. I am grateful to John Millen for taking photographs and providing assistance on behalf of the Denman Conservancy Association. A special thanks to Gary Luney, grandson of Gerald and Laura Lindsay Dickson, for sharing his knowledge of family history.

© Diana Pedersen

Please cite as follows: Diana Pedersen, “‘Salmon Fishing on a Large Scale,’” An Angler’s Paradise: Sportfishing and Settler Society on Vancouver Island, 1860s-1920s (blog), August 4, 2017, https://anglersparadise.wordpress.com/2017/08/04/salmon-fishing-on-a-large-scale.

Pingback: Lindsay Dickson Nature Reserve History | Denman Conservancy Association